Why are e-retailers indifferent to profit?

By Karan Choudhury & Alnoor Peermohamed|Business Standard | June 10, 2014

While making an all-out pitch to capture more and more of the total retail pie, they are willing to sacrifice profitability for growth

A growing number of Indians are fast turning into full-time online shoppers, buying everything from books to apparel, home decor and electronic devices at the click of a button. As their tribe grows rapidly, top e-retailers are threatening to dwarf the revenues of brick-and-mortar rivals - at least in some categories for sure. CLSA reckons e-commerce (excluding travel) has crossed the $3-billion mark. Private equity funds have bought into the story and are pouring large sums of money into it.

A growing number of Indians are fast turning into full-time online shoppers, buying everything from books to apparel, home decor and electronic devices at the click of a button. As their tribe grows rapidly, top e-retailers are threatening to dwarf the revenues of brick-and-mortar rivals - at least in some categories for sure. CLSA reckons e-commerce (excluding travel) has crossed the $3-billion mark. Private equity funds have bought into the story and are pouring large sums of money into it.However, none of the big e-retailers is anywhere close to making profits, years after being in business. (Flipkart and Myntra - the two have merged - have been around since 2007, while Snapdeal opened in 2010 and Jabong in 2012.) These are all closely-held companies and their financials are not made public. But almost all of them admit to being in the red. Some analysts compare it to the dotcom bubble of the 1990s, and wonder if good money is once again being thrown after bad.

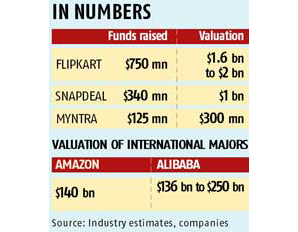

Indian e-retailers cite the example of Amazon, the American online behemoth, which took six years to break even after starting operations in 1995. In 2013, it reported net earnings of $274 million on sales of $74.45 billion - a margin of a little over 0.3 per cent. For the next quarter, it has forecast flat revenue and a loss that could touch $455 million. Analysts say that it is Amazon's long-term vision and its growth plans that pushed the company's valuation to as much as $140 billion in 2013.

Like Amazon, Indian e-retailers like Flipkart, Myntra and Snapdeal shrug off any talk of profit because they are in growth mode right now. As for valuation, Flipkart was pegged at between $1.7 billion and $2 billion recently, and Snapdeal at $1 billion. "We are not denying that being profitable is an important milestone for any company. However, the timing differs from business to business," Flipkart co-founder & CEO Sachin Bansal says. For Flipkart, which has raised an estimated $750 million from private equity funds so far, the current focus is on scaling up the business and improving user experience, according to Bansal. "Our investors also believe in our vision. Profitability will happen in its own time."

Books and beyond

Flipkart, which started off as an online bookstore seven years ago and has grown much beyond that ever since, is building technology that can handle ten times the traffic it's getting right now. "This requires change in everything from the website to the delivery mechanisms. Each phase of our growth will require further development of the existing technology," Bansal says. The e-retailer will be in an investment phase for at least another 18 months or so.

Myntra, the fashion portal that was acquired by Flipkart last month for over $300 million, has also shifted its stance from showing interest in profitability to apparent indifference. Myntra co-founder & CEO Mukesh Bansal calls it "a conscious choice between profitability and growth". Myntra, which has raised $125 million in several rounds so far, wanted to use the funds for brand-building, technology and backend operations.

Snapdeal, a hardcore marketplace player like China's Alibaba, also claims it does not want to be on the profit track yet. Maybe after two years or so, it could think on those lines. Snapdeal CEO Kunal Bahl says: "It is important to focus on economics rather than profitability." Profitability, according to him, is a choice, but not economics. Bahl says Snapdeal could have generated profits by now, but that's not the focus yet. "If you want to grow faster, you must delay profitability." Snapdeal has raised around $340 million in five rounds of funding so far.

It's another matter that Alibaba, a company that every Indian e-commerce player wants to follow now, is sitting on profits unheard of in this industry. Alibaba, which recently announced its plans to list the company on the stock market, disclosed in its prospectus with the Securities & Exchange Commission a profit of $2.8 billion for the nine months ended December 2013 on revenue of $6.5 billion. The Chinese e-retailer is valued at $136 billion to $250 billion.

Marketplace, where an e-retailer does not own the inventory but allows individual businesses to sell their products on its website, the model followed by Alibaba, is more profitable. On the other hand, the conventional inventory-based format that Amazon works on is supposed to be a revenue guzzler because of the heavy investment it requires in setting up warehouses and storage space. While Snapdeal began as a marketplace player, Flipkart recently shifted to that model after working on inventory format since launch. As foreign direct investment (FDI) is not permitted in e-commerce (read inventory model), Amazon also launched a marketplace business in India last year. There are no FDI restrictions in marketplace.

Explaining why profits are late to come by in e-commerce, Deloitte India Senior Director Gaurav Gupta says logistics and inventory costs weigh on companies' financials in the sector. E-retailers cannot hold inventory in many cities because the demand beyond metros is still not significant and is scattered, which in turn increases their logistics cost because supply chains become complex and difficult to maintain. Also, over 80 per cent of the deliveries happen through airlines and the cost cannot be transferred to the buyer because of the price war in e-retail and the race to acquire buyers.

From red to green

So, how will profits come then? "The companies will have to wait for the demand to go up that could boost volumes and help them manage supply chain and inventory more efficiently. The eco-system is still at a nascent stage," says Gupta. Though leading e-commerce companies boast of $1billion gross merchandise value targets, these are just the value of the products sold on the website, not their margins. That explains why most e-retailers are not profitable operationally, says Milan Sheth, partner and technology sector leader, EY.

Won't the non-profitable business mean e-retailers will one day go bust, like the dotcom sector in the early 2000s? Bahl of Snapdeal disagrees: "Whatever closures had to happen, have happened already." There were around 900 e-retailers as recently as 2011. Now just about four to five players remain, other than the smaller niche companies, says Bahl. He adds that natural consolidation will happen in e-commerce, quite like in telecom. "There will be significant capital consolidation around companies who have shown scale."

Of course, a lot of the recent aggressive funding has to do with Amazon's entry into India, though no Indian company would admit it. After Flipkart's acquisition of Myntra in May, Sapient India Managing Director Rajdeep Endow had said: "Globally, it is established that scale is essential for driving profitability for multi-brand online retailers. With this acquisition, I expect Flipkart and Myntra to be able to reduce costs, especially in logistics and distribution, currently a significant cost head. Two, this consolidation also provides them with greater muscle against the imminent threat of Amazon."

With all eyes on growth and not so much on profitability, e-retail is making an all-out pitch to capture more and more of the total retail pie in India estimated at $600 billion. From around $3.1 billion now, e-retail is poised to touch $22 billion in five years, says CLSA. But e-retailers are projecting a market of $60 billion to $70 billion by 2020.

Advertisement